When we place a new filling, crown or any other restoration, the final and most critical step is adjusting a new tooth to your bite. While it may not look like much from the outside, proper bite alignment is what determines whether a restoration will function comfortably for years or gradually create problems that extend beyond a single tooth.

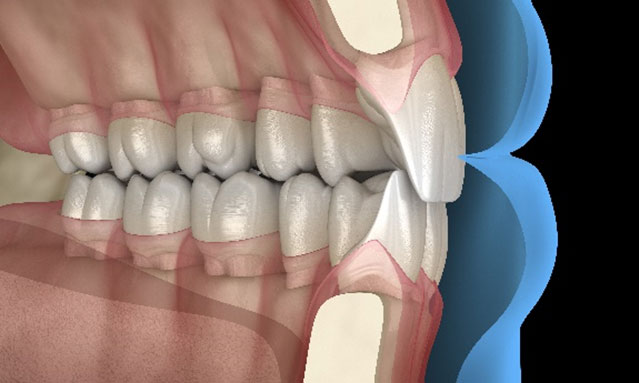

The surfaces where teeth meet are not flat. Every tooth has a unique anatomical design made of cusps, grooves, ridges, and contact points that fit together like puzzle pieces. These features guide how your teeth engage and how your jaw moves side-to-side and front-to-back providing balance, stability and proper functionality of your entire masticatory system. Your bite is individual, determined by many factors and that is why every restoration must be shaped specifically for your mouth.

So, why your bite must be perfect after your new filling or crown? Posterior (back) teeth contain supporting cusps that fit into opposing grooves and help determine the height and stability of the bite. But they do not only determine how high or low the teeth meet — they also help establish the vertical height between the upper and lower jaws, which directly influences the space within the temporomandibular joints (TMJs). When a new restoration is placed even slightly too high or too low, it inevitably create a new contact point that the jaw must accommodate at each level. This forces the chewing muscles to work differently to close the bite and re-establish stability for the entire chewing system. Other cusps overlap and guide jaw movement, acting like rails that direct the lower jaw during function.

When this harmony is maintained, the chewing muscles function efficiently without tension, tooth surfaces glide rather than grind, and the articulating surfaces of the TMJs remain protected from excessive wear. The entire system operates within its physiological limits, supporting long-term health and durability of all structures. But if even one small part is out of alignment, the system must compensate — and compensation comes at a cost.

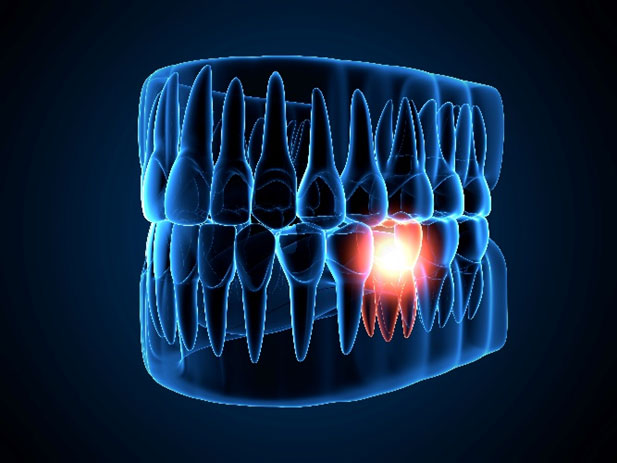

A new restoration does not adapt to the bite — the bite adapts to the restoration. In case of interocclusal balance violation it can lead to multiple complications like soreness or sensitivity in the restored tooth, persistent “high spot” feeling, cracking or wear on other teeth, shifting of the jaw to find a new stable position with long-term bite changes and new areas of imbalance. In extreme cases some patients might experience morning headaches due to muscle overwork. That is why a good restoration isn’t finished until your bite is right.

The body will always seek stability. If a restoration changes the balance of contact, the jaw may shift to find comfort, potentially altering the entire occlusal system over time. In other words, a small change on one tooth can trigger a system-wide response. This is why fine-tuning occlusion isn’t just about comfort — it protects the entire chewing system. A small adjustment will prevents big dental problems.

Unless bite modification is intentionally planned as part of the treatment strategy, a new restoration should feel natural — as though nothing has changed. The goal is for the patient to leave with the same comfortable occlusion they walked in with, without awareness of a “new” tooth or altered contact.